Persistent connections with gen_statem

Our applications often interact with external systems. In many cases, we need a persistent connection to one or more of these external services. For example, if your application makes continuous use of a database, you'll likely want to stay connected to such database so that you can avoid spending time and resources connecting and disconnecting each time you perform a request. With Erlang and Elixir, the natural abstraction to maintain a persistent connection is a process. In this post, we'll have a look at how we can take advantage of the gen_statem behaviour to write state machine processes that act as persistent connections to external systems.

This article is an evolution of a previous article posted on this blog, "Handling TCP connections in Elixir". In that article, I describe how to build a connection process that talks to a Redis server over TCP. Instead of gen_statem (which wasn't available at that time), I use the connection library by James Fish, but the concepts are similar. If you're interested in the TCP interactions more than you are in gen_statem, read that article first. What I describe here is an evolution of the old implementation that doesn't require external dependencies and that nicely shows a practical use case for many of the features that gen_statem provides.

Note: I'm more used to Elixir and its syntax, so that's what I'm going to use here. However, I won't use almost any Elixir-specific features, so the article should also be readable for folks that are more comfortable with Erlang. If you want to follow along with the finished Erlang code for the state machine we'll build, look at the Gist containing the final implementation in Elixir and Erlang.

The connection "manager"

During the blog post, we'll build a connection process that maintains a persistent TCP connection to a database.

It's important to understand the design and purpose of our connection process. This process is not the connection to the database itself but only a wrapper around the connection. This means that if the connection itself goes down, our process should stay alive and try to reconnect while replying with errors to clients that try to make requests. While a catchphrase of the Erlang and Elixir world is "let it crash", erroneous conditions such as the TCP connection going down are known in advance and our system should strive to be resilient when they happen. TCP errors are not errors for our connection process, they're just another event happening in the system. This design decision is a powerful one because it leads us to a stable and resilient process that our system can rely on, regardless of the state of the actual connection.

A side effect of the design of the connection process so that it's independent of the state of the connection is that we don't need to establish the TCP connection synchronously when starting up our process. We can start our connection process and return a PID right away, start establishing the connection in the background, and then act as if the connection is "broken" until the connection is established. After all, our connection process and application will need to deal with the connection being broken at some point, so there's often no reason to require synchronous connecting.

The ideas briefly mentioned above come from an article by Fred Hebert, "It's about the guarantees", which does a great job at explaining why the design I discussed works well especially in Erlang and Elixir applications.

gen_statem primer

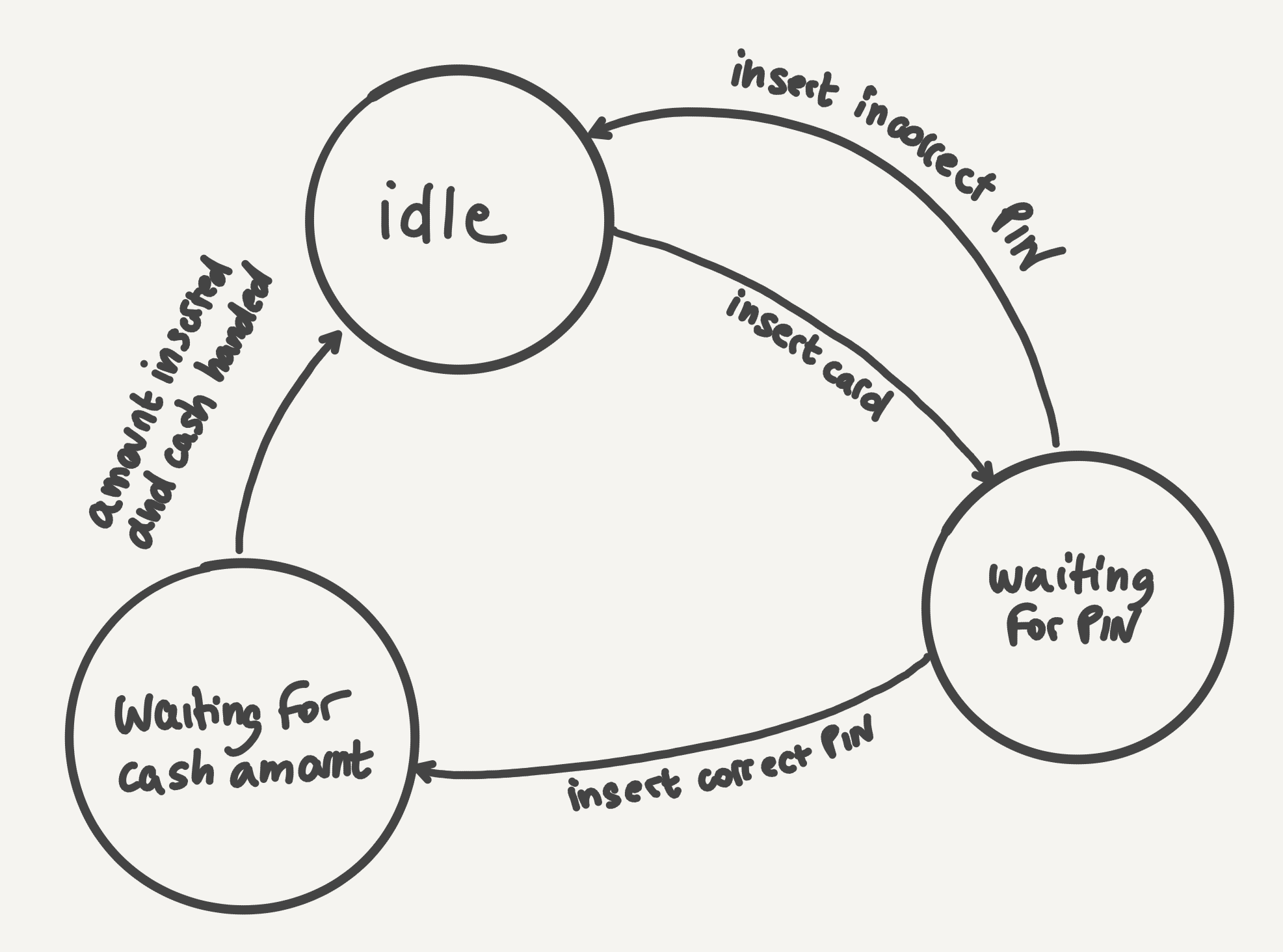

gen_statem is an OTP behaviour (like GenServer) that was introduced in OTP 19. Like its name suggests, it's an abstraction over a state machine. A common example of a state machine is an ATM:

There are states that the ATM can be in (like waiting_for_pin or requesting_cash) and events that cause state transitions, that is, moving from one state to another state (or to the same state).

gen_statem mirrors the design of a state machine very closely. Essentially, you have something similar to a GenServer, where you have callbacks and events like user calls or messages. In a gen_statem module, however, you have a state which represents the state machine's state and a data term that represents information that the state machine is carrying around. The "data" in a gen_statem is what we usually call the "state" in a GenServer (this is confusing, bear with me).

The gen_statem states are represented through functions: in the ATM machine, you would have a waiting_for_pin/3 function (with one or more clauses) to handle events in the waiting_for_pin state, and so on for the other states. The return value of state functions determines what the state machine should do next and looks something like this:

-

{:next_state, next_state, new_data, actions}to transition to the next statenext_state.new_datais the new data of the state machine andactionsis a list of actions, like firing off internal events, setting up timers, or replying to calls. We'll have a better understanding of actions as we go along. -

{:keep_state, new_data, actions}to remain in the same state.new_dataandactionsare the same as described for:next_state.

The API that :gen_statem exposes is actually a bit complex. A symptom of this is that there are many more return values than the two mentioned above, but most of them end up being simplifications of these two. For example, you can return {:keep_state, new_data} instead of {:keep_state, new_data, []} if you don't want to execute any actions. We'll try to use whatever fits best in each instance.

It's all about the connection

We're going to use TCP with :gen_tcp to connect to the database. We'll send requests through the socket and then asynchronously receive responses from the database. The clients calling our connections will wait synchronously on responses to the requests that they sent, but our connection will be able to handle multiple requests from different clients concurrently. We'll assume our fictional database has a protocol that expects each request to have an ID and that tags each response with the ID of the corresponding request. This will allow our state machine to maintain a map of request ID to requesting process for in-flight requests. When a response arrives, we can retrieve the caller waiting for it from this map.

Designing the state machine

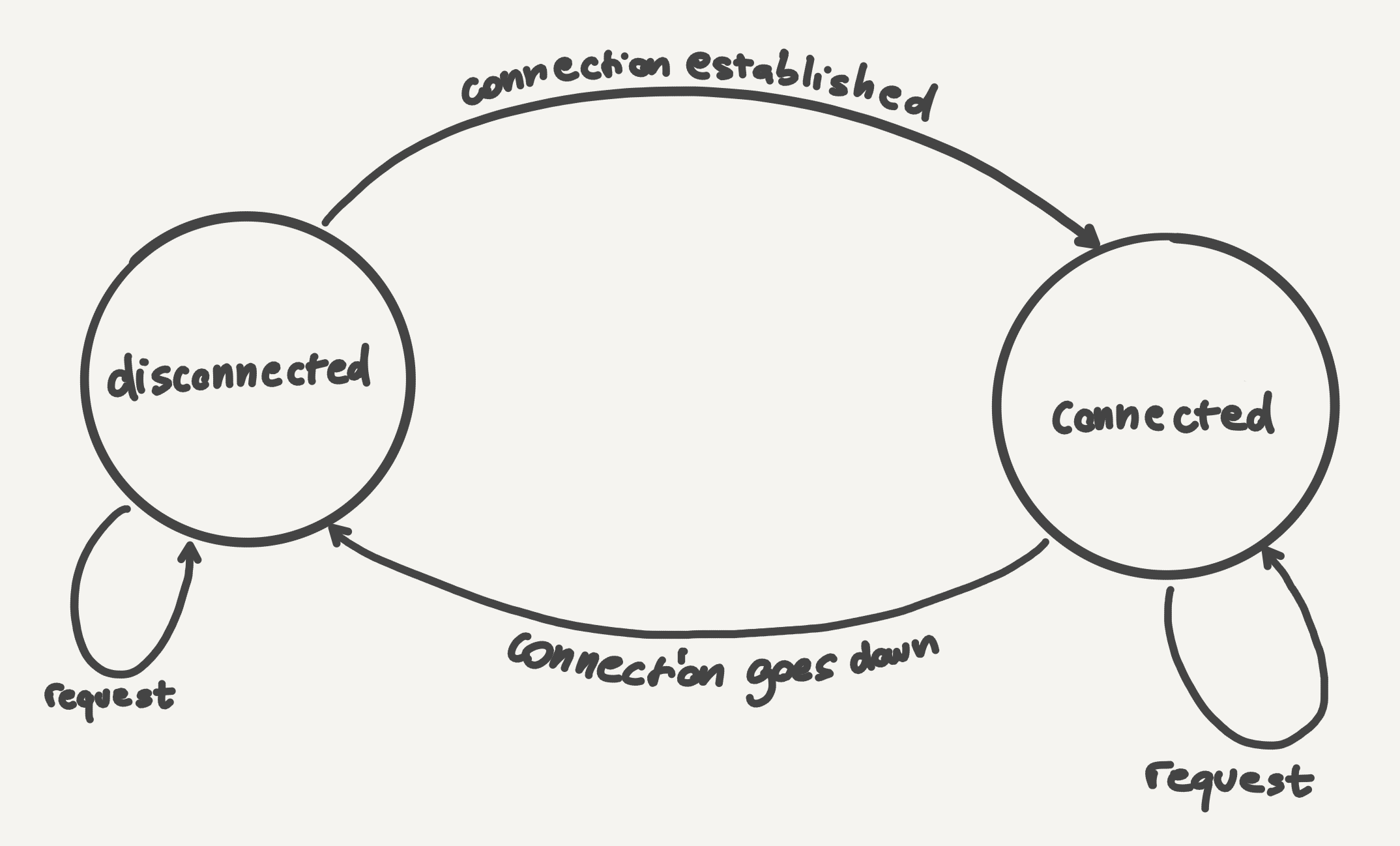

Let's start with designing the states of our connection. We already figured out that there's going to be a disconnected state for when the TCP connection is down. This will also be the starting state since we'll start as disconnected and then try to connect the first time as mentioned at the beginning of the article. We only need one more state, the connected state, for when the TCP connection is alive and well. The next step when designing the state machine is figuring out what events cause the state machine to transition from one state to another. In our case, we can think of these events causing state transitions:

-

The TCP connection goes down — this makes the state machine transition from the

connectedstate to thedisconnectedstate. -

The TCP connection is established successfully — this makes the state machine from

disconnectedtoconnected.

Then, we have events that don't cause state transition. In our case, that's only requests from clients.

A helpful habit when designing state machines is to draw a diagram of the state machine. This lets us visualize the states and state transitions at a glance.

Implementing the state machine

Let's turn this diagram into a functioning gen_statem. The first thing to do is to create a Connection module and specify that it's an implementation of the :gen_statem behaviour. We'll also define an internal struct that we'll use as the data carried by the state machine. The data will contain the host and port to connect/reconnect to, the TCP socket, and a map of request ID to caller waiting for a response.

defmodule Connection do

@behaviour :gen_statem

defstruct [:host, :port, :socket, requests: %{}]

# Ignore this for now. We'll see what this is about later on.

@impl true

def callback_mode() do

:state_functions

end

def start_link(opts) do

host = Keyword.fetch!(opts, :host)

port = Keyword.fetch!(opts, :port)

:gen_statem.start_link(__MODULE__, {String.to_charlist(host), port}, [])

end

endAs we mentioned, the state machine starts in the disconnected state. Similarly to a GenServer, when you start the state machine process, start_link won't return until the init/1 callback that both GenServer and gen_statem provide returns. We want to return from init/1 right away and then establish the connection in the background. gen_statem provides us with a perfect tool for this: internal events. In our case, we can return from init/1 right away and generate an internal :connect event that tells the state machine to initiate connection. Let's start with implementing the init/1 callback.

def init({host, port}) do

data = %__MODULE__{host: host, port: port}

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:ok, :disconnected, data, actions}

endAs you can see, the return value of init/1 specifies that the first state to transition to is the :disconnected state. The only action we want to execute is :next_event which fires off an event. Events have a type and a term attached to them. For example, an Elixir message coming to the state machine process has the event type as :info and the term as the message itself. In our case, we fire off an internal event that has the type :internal and the term :connect.

The state machine states are implemented as functions named as the state. So in our case, the first function to implement is disconnect/3. State functions are called with the event type as the first argument, the event term as the second argument, and the data as the third argument.

def disconnected(:internal, :connect, data) do

# We use the socket in active mode for simplicity, but

# it's often better to use "active: :once" for better control.

socket_opts = [:binary, active: true]

case :gen_tcp.connect(data.host, data.port, socket_opts) do

{:ok, socket} ->

# We omit the actions as there are none.

{:next_state, :connected, %{data | socket: socket}}

{:error, error} ->

Logger.error("Connection failed: #{:inet.format_error(error)}")

# This is the same as {:keep_state, data, actions} but makes it clear

# we're not changing the data.

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:keep_state_and_data, actions}

end

endIf the connection is established successfully, we store the socket in the data and move to the :connected state. If there's an error connecting, we stay in the :disconnected state with the same data and fire the internal :connect event again. This means that we'll try to reconnect right away and might end up in a failed connection loop. We'll fix this later on by introducing back-offs.

Now that we're in the :connected state, let's handle the connection going down so that we'll have all the state transitions. Since our TCP socket is in active mode, we'll get a {:tcp_closed, socket} message when the connection goes down (let's ignore {:tcp_error, socket, reason} for now).

def connected(:info, {:tcp_closed, socket}, %{socket: socket} = data) do

disconnect(data)

end

# Let's use a helper function, it will come in handy later.

defp disconnect(data) do

Logger.error("Connection closed")

data = %{data | socket: nil}

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:next_state, :disconnected, data, actions}

endWe return to the :disconnected state and immediately fire off an internal :connect event so that we'll try to re-establish the connection right away. This is the same as what happens when we can't connect for now.

Handling requests

Now, we need to handle requests from clients and data coming back from the database. These requests will be made through request/2:

def request(pid, request) do

:gen_statem.call(pid, {:request, request})

endThe event type that results from a :gen_statem.call/2 call is {:call, from}. from identifies the caller, similarly to the from argument in handle_call/3 for GenServers. The event content is the request itself, in our case {:request, request}.

A request can come in either the :connected or the :disconnected state and it never causes a state transition. When a request comes in the :disconnected state, we reply with {:error, :disconnected} right away. Replying is another action that we can perform.

def disconnected({:call, from}, {:request, request}, data) do

actions = [{:reply, from, {:error, :disconnected}}]

{:keep_state_and_data, actions}

endWhen a request comes in the :connected state, we issue the request to the database and store the caller under the request ID in our request map. request here could be anything, but let's imagine it's a map that contains a :id key holding the ID of the request. If there's an error sending, we close the socket and go back to the disconnected state.

def connected({:call, from}, {:request, request}, data) do

case :gen_tcp.send(data.socket, encode_request(request)) do

:ok ->

data = %{data | requests: Map.put(data.requests, request.id, from)}

{:keep_state, data}

{:error, _reason} ->

:ok = :gen_tcp.close(socket)

disconnect(data)

end

endSince our TCP socket is in active mode, packets sent by the database will arrive as messages to the state machine. A {:tcp, socket, data} message can only come in the :connected state, so we can skip the additional disconnected/3 clause to handle TCP packets. For simplicity, we're going to assume that a packet always contains a single complete response so that we can avoid buffering.

def connected(:info, {:tcp, socket, packet}, %{socket: socket} = data) do

response = decode_response(packet)

{from, requests} = Map.pop(data.requests, response.id)

# :gen_statem.reply/2 can be used to manually reply to a

# :gen_statem.call/2 (similarly to GenServer.reply/2).

:gen_statem.reply(from, {:ok, response})

{:keep_state, %{data | requests: requests}}

endPerforming actions when entering a state

You might notice there's a bug in our implementation: when we disconnect, we don't notify the clients that are waiting for a response. To do that, we can modify the disconnect/1 helper function:

defp disconnect(data) do

Logger.error("Connection closed")

Enum.each(data.requests, fn {_id, from} ->

:gen_statem.reply(from, {:error, :disconnected})

end)

data = %{data | socket: nil, requests: %{}}

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:next_state, :disconnected, data, actions}

endThis works, but :gen_statem provides a possibly better way to perform common clean up code when disconnecting: state enter events. It's enough to change the callback_mode/0 callback we implemented initially:

@impl true

def callback_mode() do

[:state_functions, :state_enter]

endNow, :gen_statem will call new_state(:enter, old_state, data) every time the state machine transitions from old_state to new_state. If we transition from :connected to :disconnected then disconnected(:enter, :connected, data) will be called. This is ideal for our use case, as we can now remove the disconnect/1 helper function and implement the disconnected/3 clause that handles the :enter event.

def disconnected(:enter, :connected, data) do

Logger.error("Connection closed")

Enum.each(data.requests, fn {_id, from} ->

:gen_statem.reply(from, {:error, :disconnected})

end)

data = %{data | socket: nil, requests: %{}}

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:next_state, :disconnected, data, actions}

endThis allows us to just move to the disconnected state when we want to disconnect, and the state enter clause will take care of replying to waiting clients and cleaning the data up. Note that since :disconnected is our first state, the :enter event will fire the first time with the old state being :disconnected as well. We can just do nothing in that case.

def disconnected(:enter, :disconnected, _data) do

:keep_state_and_data

endThe enter callback is called for every state transition, so we need to handle it in the :connected state as well. We don't want to do anything when entering that state.

def connected(:enter, _old_state, _data) do

:keep_state_and_data

endTimeouts for back-offs

We've now got a pretty neat connection process that holds the TCP connection to our database and is able to reply to clients regardless of the state of such connection. However, in the code we built we try to reconnect as soon as the connection goes down or we fail to connect. This is usually a terrible idea, because if a connection goes down there's a good chance it won't be up right away, especially if we also fail to reconnect. A common technique to avoid frequent connection attempts is to wait a back-off period before attempting reconnections. When the connection goes down or we fail to connect, we'll wait a few hundred milliseconds before trying again.

:gen_statem has the perfect tool to implement this: timeouts. One of the possible actions you can return from state functions is {:timeout, timeout_name}, which you can use to set a timeout with some term attached to it after a given amount of time. When the timeout expires, an event of type {:timeout, timeout_name} is fired.

Let's start by setting the timeout when we enter the disconnected state.

def disconnected(:enter, :connected, data) do

# Same as before: logging, replying to

# waiting clients, resetting the data.

actions = [{{:timeout, :reconnect}, 500, nil}]

{:keep_state, data, actions}

endOur timeout will fire after 500 milliseconds We use nil as its term since we're not carrying any information alongside the timeout other than its name (:reconnect). When the timeout expires, we need to handle it in disconnected/3:

def disconnected({:timeout, :reconnect}, _content, data) do

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:keep_state, data, actions}

endWhen the :reconnect timeout is fired, we just fire the internal :connect event so that we end up trying to reconnect. This removes repetition in the code and hides the plumbing of setting up timeouts manually.

Exponential and random back-off

Without going too much into detail, a fixed back-off time might not be the best idea. Imagine you have one hundred TCP connections established with the database. If the database goes down, all those connections will go down at the same time and will try to reconnect every 500 milliseconds, all at the same time. Part of the fix is to increase the back-off exponentially so that we can avoid situations where the database is down for a while and all connections try to reconnect very often. Then, we can add some random interval of time before reconnecting for each connection so that we avoid all the connections trying to reconnect at the same time. In code, the formula for the next back-off (given the previous back-off) can be something like:

next_backoff = round(previous_backoff * 2)

next_backoff + Enum.random(-1000..1000)Dynamic state

The last feature of :gen_statem that I want to explore is dynamic state. Let's see how that could be needed in our state machine. Right now, the :socket field in the data is only present in the :connected state and nil the rest of the time. This information perfectly mirrors the state but it's encoded in the data and has to be managed side by side with the state and state transitions. It would be nice if we could stick the socket alongside the :connected state, wouldn't it? Well, we can do exactly that with "handle event" functions instead of state functions. With "handle event" functions, the state is not a simple atom (like :connected or :disconnected) anymore, but it can be any term. However, this means we can't use functions to represent the state: we'll have to use a common handle_event/4 callback to handle all events in all state. We'll pattern match on the state to mimic what we were essentially doing with the names of the functions.

The first thing to do to use "handle event" functions is change :state_functions to :handle_event_function in callback_mode/0:

@impl true

def callback_mode() do

[:handle_event_function, :state_enter]

endWe won't rewrite the whole state machine, but just a small snippet. Let's see how we can now handle the internal :connect event in the :disconnected state. For the :disconnected state, we'll use the :disconnected atom since we don't want to carry any information with it.

def handle_event(:internal, :connect, :disconnected, data) do

socket_opts = [:binary, active: true]

case :gen_tcp.connect(data.host, data.port, socket_opts) do

{:ok, socket} ->

{:next_state, {:connected, socket}, data}

{:error, error} ->

# Same as before.

actions = [{:next_event, :internal, :connect}]

{:keep_state_and_data, actions}

end

endNow, instead of moving to the :connected state in case of successful connection, we move to the {:connected, socket} state. This means that the socket is tied to the "connected" state and doesn't exist in the :disconnected state.

"Handle event" functions are powerful. They set :gen_statem aside from its previous version, :gen_fsm (which is now deprecated). :gen_fsm would only let users implement finite-state machines (hence the fsm in the module name), but :gen_statem with "handle event" functions lets users implement a generic transition system.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored a way to build processes acting as persistent connections to the outside world using :gen_statem. We learned how to build a real-world state machine and how to use a bunch of features provided by :gen_statem to avoid repetition and simplify our implementation. For more information on the TCP interaction bits of this article, check out "Handling TCP connections in Elixir". If you're interested in the reasoning behind the design of the persistent connection, refer to "It's about the guarantees".

If you're interested in the whole code for the state machine that we built, you can find it as a Gist. In the Gist there are both the Elixir version we built and an Erlang version if you're more comfortable with Erlang.