How to Async Tests in Elixir

Recently, I've been focusing a lot on the health of our test suite at Knock. Fast, reliable tests are a boost for confidence and developer happiness, so I naturally care a lot about this. I've been wrestling with two main things: slow tests, and flaky tests. My sworn enemies.

The good news here is that I believe that the "solution" to both these issues are proper, robust asynchronous tests. When tests are asynchronous, single tests can even be somewhat slow because you have ways to overcome that. You can scale horizontally with more parallel tests, more cores, and so on. You can split up test cases and parallelize slow tests even more. What about flakiness? Right. In my experience, so much of the flakiness comes from either improperly-written asynchronous tests or slow timeouts and assertions on messages. Go fix the latter, I have no silver bullet for that.

This post is about beautiful, elegant, robust asynchronous tests in Elixir. It's also a kind of ode to OTP concurrency and about parallel-forward thinking and maybe some other made up words.

When Is It Hard to Parallelize Tests?

First of all, throw tests for pure code out of the window. We don't care about those. Say I have a function that checks if a string is valid base64 data:

def valid_base64?(string) do

match?({:ok, _}, Base.decode64(string))

endNothing that has to do with testing it in parallel here. This has no side effects. It's as pure as the eyes of a golden retriever puppy. Test this in parallel to your heart's desire, even though I doubt this is the kind of tests that are making your test suite slow.

So, side effects are what make it hard to turn tests async? Yeah, in some way. That, but in particular singletons. We'll see in a sec, let's go through why some side effects are easy to test in parallel.

Maybe you want to test a function that writes something to a file. Writing to the filesystem is a side effect, no doubts, and a destructive kind (the scariest kind!). But, as long as you're smart about where to write, you can kind of get away with it:

test "writes output to a file" do

filename = "#{System.unique_integer([:positive])}.txt"

output_path = Path.join(System.tmp_dir!(), filename)

MyMod.calculate_something_and_write_it(output_path)

endCool, you can run many of these tests in parallel and they won't step on each other's toes, even though the system under test is all about the side effect.

Singletons Are the Bane of Async Tests

Back to singletons. A singleton is something which you have a single instance in your system. Those are hard to test. You want an example that you probably know about? I'll give you one. That sick, deprived Logger. Yucksies. Logger is a singleton in the sense that you usually only log to stdout/stderr and use ExUnit.CaptureLog functions to assert on logged content. But if two pieces of code log at the same time—because spoiler, it's two tests running concurrently and executing some code that logs something—:vomiting_face:. Who captures what. It's undeterministic (well until you have to patch a hotfix in production, then it's whatever makes at least one of the tests fail in CI).

You're likely to have an assorted, colorful bunch of other singletons in your system. The GenServers ticking every few seconds and doing godknowswhat™. The ETS tables doing the cachin'. You know the ones.

But fear no more, there is a fix for almost all situations. It's based on LLMs, agentic processing, and the power of AI. Nah just kidding, it's ownership (plus getting rid of singletons, lol).

The getting-rid part first.

No More Singletons

Design your processes and interfaces and applications so that singleton-ness (singleton-icity? singleton-ality?) is optional. Say I have a process that buffers metric writes to a StatsD agent so as to be Very Fast™ and out of the way of your system.

defmodule MetricsBuffer do

use GenServer

def start_link([] = _opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, :no_args, name: __MODULE__)

end

def increment_counter(name) do

GenServer.cast(__MODULE__, {:metric, :counter, name})

end

# ...

@impl GenServer

def handle_cast({:metric, type, name}, state) do

{:noreply, buffer_metric(state, type, name)}

end

endBad news: that's a singleton if I've ever seen one. The sneaky name: __MODULE__ is the culprit. If you register the process with a (very "static") name, and then cast to it by name, then there can only be one of those processes in the system. If two concurrent tests emit a metric through MetricsBuffer, you just lost the ability to test those metrics as you'll have unpredictable results depending on the order those tests execute stuff in.

I don't know of a perfectly clean way to solve this. "Clean" in testing usually involves stuff like "don't change your code to make tests easier" and stuff like that. I'd rather have some test code in there and write tests for this, then to not write tests altogether, so let's power through.

De-singleton-ifying

The simplest approach to take in these cases, in my opinion, is to make your singleton behave like a singleton at production time, but not making it a singleton at test time. You'll see what I mean in a second.

defmodule MetricsBuffer do

use GenServer

- def start_link([] = _opts) do

+ def start_link(opts) do

- GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, :no_args, name: __MODULE__)

+ name = Keyword.get(opts, :name, __MODULE__)

+ GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, :no_args, name: name)

end

- def increment_counter(name) do

+ def increment_counter(server \\ __MODULE__, name) do

- GenServer.cast(__MODULE__, {:metric, :counter, name})

+ GenServer.cast(server, {:metric, :counter, name})

end

# ...

endNow, you're making the GenServer name optional and defaulting to __MODULE__. That's what it'll use in production. In tests, you can start it with something like

setup context do

server_name = Module.concat(__MODULE__, context.test)

start_supervised!({MetricsBuffer, name: server_name})

%{metrics_server: server_name}

endNice, but there are some issues. The main one is that you have to explicitly reference that new name everywhere in your test case now. But you might not be testing the public API for MetricsBuffer directly—maybe your code-under-test is calling out to that. How do you pass stuff around? Turns out, you combine this technique with ownership.

Ownership + async: true = :heart:

First, a few words to explain what I’m talking about. The idea with ownership is that you want to slice your resources so that each test (and its process) own the resources. For example, you want each test process to "own" its own MetricsBuffer running instance. If the owned resources are isolated from each other, then you can run those tests asynchronously.

There are a few ways you can build ownership into your code. Let's take a look.

At the Process Level: nimble_ownership and ProcessTree

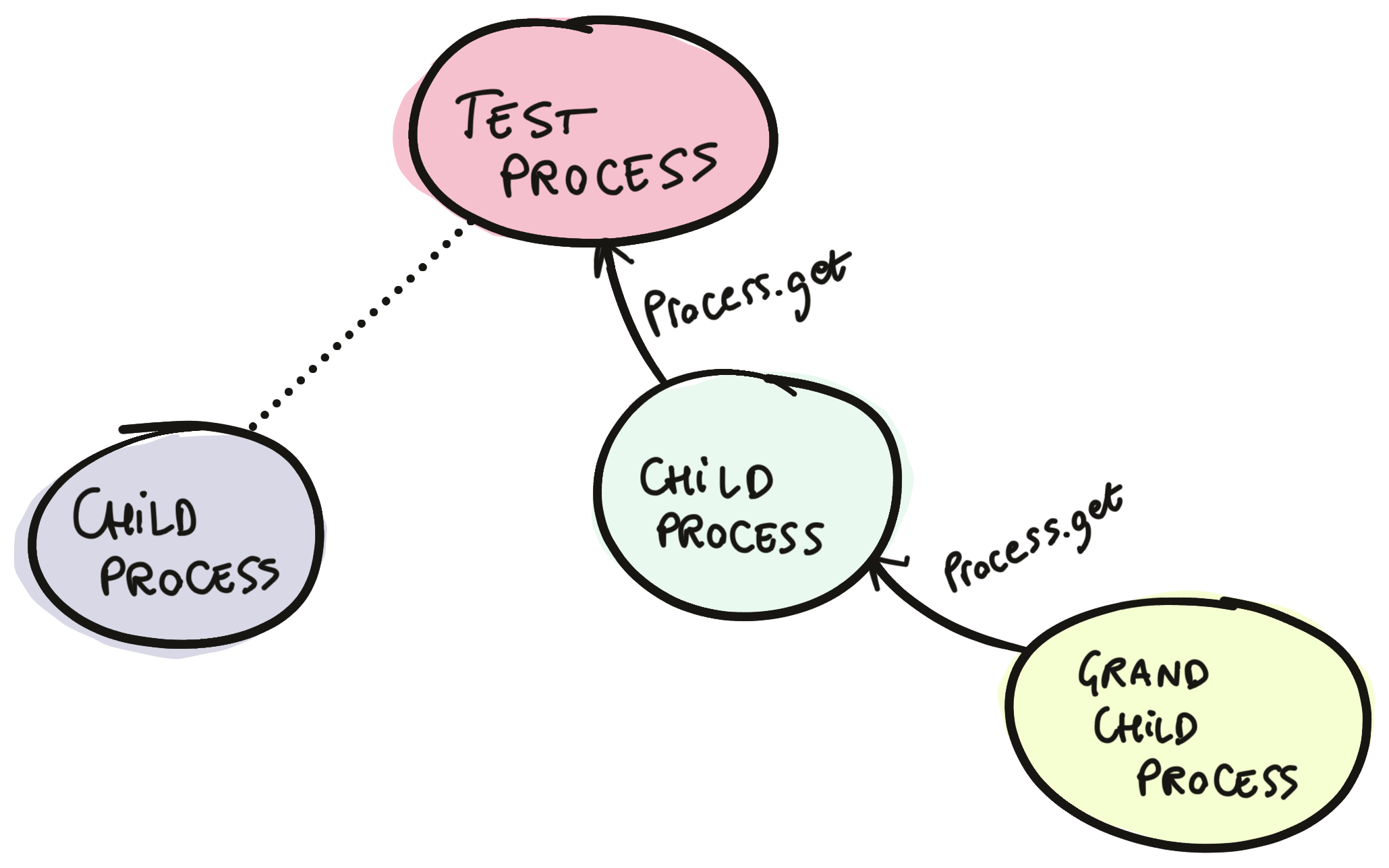

Ownership (in this context) is essentially always at the process level. Each test process owns the resource. However, the important caveat is that you often want "child processes" of the test process to be allowed to use the resource too. Basically, you want this to work:

test "async metrics" do

Task.async(fn ->

# ↓ Should still use the metrics server owned by the test process

code_that_reports_metrics()

end)

endwithout necessarily passing the MetricsServer around (which is often a pain to do). There's a pretty easy solution that, however, requires you to modify your MetricsServer code a bit.

ProcessTree

I’m talking about a library called process_tree. Its job is pretty simple: it looks up keys in the process dictionary of the current process and its "parents". A short example:

Process.put(:some_key, "some value")

task =

Task.async(fn ->

{Process.get(:some_key), ProcessTree.get(:some_key)}

end)

Task.await(task)

#=> {nil, "some value"}This "parent lookup" is based on a few features of OTP, namely the :"$callers" process dictionary key that many OTP behaviours use as well as :erlang.process_info(pid, :parent). This turns out to be pretty reliable.

Now, the trick to have async tests here is to store the PID of the metrics server (or whatever singleton) in the process tree of your test process. Then, every "child" of your test process has access to this. In my opinion, a nice way to do this is to just slightly modify the MetricsServer code:

defmodule MetricsServer do

def start_link(opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, :no_arg, Keyword.take(opts, [:name]))

end

def increment_counter(name) do

GenServer.cast(server(), {:metric, :counter, name})

end

# ...

if Mix.env() == :test do

defp server do

ProcessTree.get({__MODULE__, :server_pid})

end

else

defp server do

__MODULE__

end

end

endThe idea is that you start your server with name: MetricsServer in your application supervisor. In tests, instead, you do:

setup do

pid = start_supervised({MetricsServer, []})

Process.put({MetricsServer, :server_pid}, pid)

:ok

endVoila! You have Solved Async Tests™.

Now, if you're worried about whether this is a "clean" solution, I get it. However, let's think through this a sec. What is it that you're doing in production that you're not testing here? I'd argue it's only the name resolution. In production, you're not testing that __MODULE__ name registration works... But that's OTP, so I trust that.

Now, ProcessTree falls short when you want to have utilities that test something about the owned resource after the test is finished. This is somewhat a common use case. The prime example is Mox. In Mox, you want to assert that the expected number of calls were received during the test, but after the test is done. Mox uses a on_exit hook for this, but when on_exit runs the test process has already exited... We need to store these expectations outside of the test process, and be able to retrieve them after the test is done. We need a resource that outlives the test.

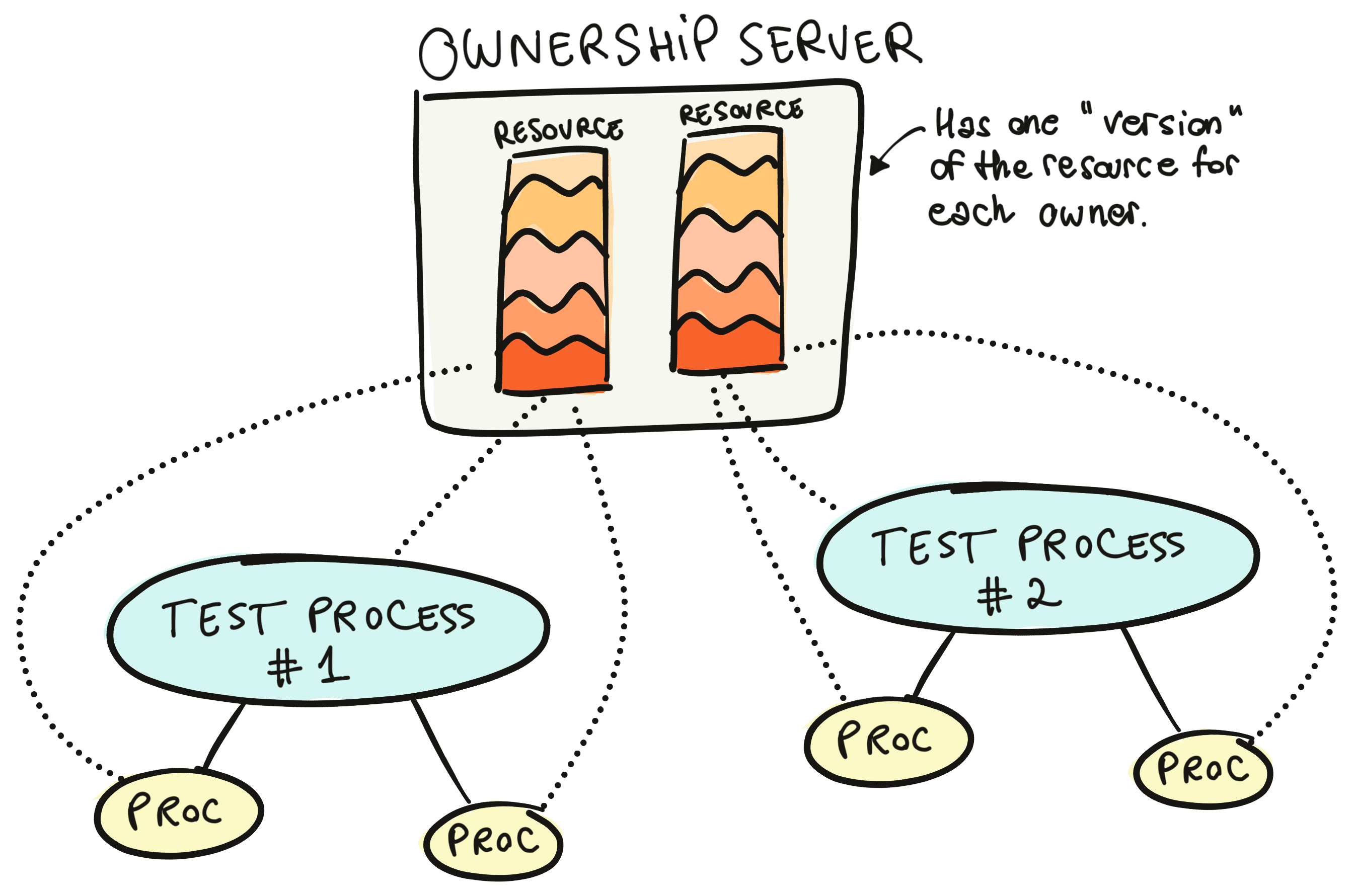

Enter nimble_ownership

nimble_ownership is a small library that we extracted out of Mox itself. Its job is to provide an "ownership server" and track ownership of resources across processes.

The ownership server can store some metadata for a given process. Then, that process can allow other processes to access and modify that metadata.

You might see how Mox uses this. Mox starts a global ownership server when it starts (Mox.Server) and stores expectations for each function in each mock module, for each process that calls Mox.expect/4. A simplified implementation could:

- Store a list of

{mock_module, function_name, implementation}tuples. - Whenever there's a call to a function in the mock module, the mock module (which is implemented by Mox) would find the tuple for the right mock module and function, and "pop" the

implementation.

Then, you'd allow other processes (like child processes) to use the mocks. The server would do something like:

defmodule MyMox do

def start_link do

NimbleOwnership.start_link(name: __MODULE__)

end

def expect(mod, fun, impl) do

NimbleOwnership.get_and_update(

__MODULE__,

_owner = self(),

_key = :mocked_functions,

fn current_value ->

new_value = (current_value || []) ++ [{mod, fun, impl}]

{new_value, :unused_return_value}

end

)

end

endThen, the generated mock modules could do something like:

def my_mocked_fun(arg1, arg2) do

{:ok, owner} =

NimbleOwnership.fetch_owner(

_ownership_server = MyMox,

[self() | callers()],

:mocked_functions

)

impl =

NimbleOwnership.get_and_update(

MyMox,

owner,

_key = :mocked_functions,

fn current_value -> pop_implementation(current_value) end

)

apply(impl, [arg1, arg2])

end

defp callers do

Process.get(:"$callers") || parents(self())

end

defp parents(pid) do

case Process.info(pid, :parent) do

{:parent, :undefined} -> []

{:parent, parent} -> [parent | parents(parent)]

end

endThe key thing here is that mock implementations are not tied to the lifecycle of the test process, nor is the ownership server. So, when the test process has exited (like in an on_exit hook), you can still access the owned resources for that exited test process and perform assertions on those.

This whole ownership thing is not super straightforward, but the nimble_ownership documentation does a good job at explaining how it works. Also, you can go dig into the Mox implementation to see how it uses nimble_ownership.

Now, there's another way of doing process-based ownership that you've likely been using.

At the Database Level: Transactions

Ecto is probably the best-known example of tracking ownership. Ecto calls it the sandbox, but the idea is quite similar. First, why this is an issue: the database is, in its own way, shared state. Say you had:

- A test that selects all rows from table

accounts. - Another test that inserts a row in the

accountstable.

Test #1 would sometimes see the new from test #2 and sometimes not. Flaky test.

So, instead of tracking a resource like a nimble_ownership server or similar, the Ecto sandbox tracks a database transaction. All DB operations in a test and in the allowed processes for that test run in a database transaction, that gets rolled back when the test finishes. No data overlap!

Ecto implements its own ownership mechanism, Ecto.Adapters.SQL.Sandbox, but the ideas are the same as the ones we discussed in this post.

At Other Levels: Whooopsie

There are some singletons that you cannot get out of having. We already mentioned Logger, for example. You could get clever with ownership-aware logger handlers and whatnot, but that's not the only common one. Another frequent suspect is Application configuration. If your code reads values from the application environment, then testing changes to those values makes it impossible to run those tests asynchronously:

def truncate_string(string) do

limit = Application.get_env(:my_app, :truncation_limit, 500)

String.slice(string, 0..limit)

end

test "truncate_string/1 respects the configured limit" do

current_limit = Application.get_env(:my_app, :truncation_limit)

on_exit(fn ->

Application.put_env(:my_app, :truncation_limit, current_limit))

end)

string = String.duplicate("a", 10)

Application.put_env(:my_app, :truncation_limit, 3)

assert truncate_string(string) == "aaa"

endThis dance is pretty common. Get the current value, make sure to set it back after the test finishes, and then change it to test the behavior. But you can see how another concurrent test changing that value would potentially break this test.

So, what are you to do in these cases? Tough luck. There's no satisfaction here. The most successful practical approach I've seen is to define an interface for Application and use mocks to have values read/written in an async-friendly way. You can use Mox, you can use Mimic, whatever floats your boat really. Just go read The Mox Blog Post first.

Practical Advice

Just a bunch of jotted-down advices:

- Hardcoded singletons are "clean" from a code perspective, but so hard to work with. Make your life easier, and think like a library author when you can: no singletons, just configurable processes. Then, these can act as a single global resource if needed.

- Try to start with

ProcessTreerather than nimble_ownership. The ownership idea is powerful but quite more complex than just climbing up the process tree to find a PID. - Abstract as much as possible into your own testing helpers. At Knock, we have quite a few

MyApp.SomePartOfTheAppTestinghelpers that weusein our tests. This facilitates abstracting what to store in the process dictionary, key names, and so on.

Conclusion

Woah, that was a lot.

First, a short acknowledgement. I've got to thank my coworker Brent, who put me onto ProcessTree and who I've designed much of what I've talked about with.

We started with what the common issues that prevent asynchronous tests are. Then, we explored solutions for:

- Limiting singletons in your system.

- Using

ProcessTreeto track resources back to a test process. - Establishing resource ownership with nimble_ownership (or Ecto's sandbox).

- Using mocks as the last resource.

Some resources to check out:

- I spoke about some of these topics a few years ago—the talk is more philosophical and high level than this post, but might be helpful.

- Testing Elixir, which goes into more detail on some of the things we discussed.

I hope this all made sense. If I can help clarify anything, leave a comment or throw an email my way. See ya!